Superstring Secrets: Hong Kong

2020

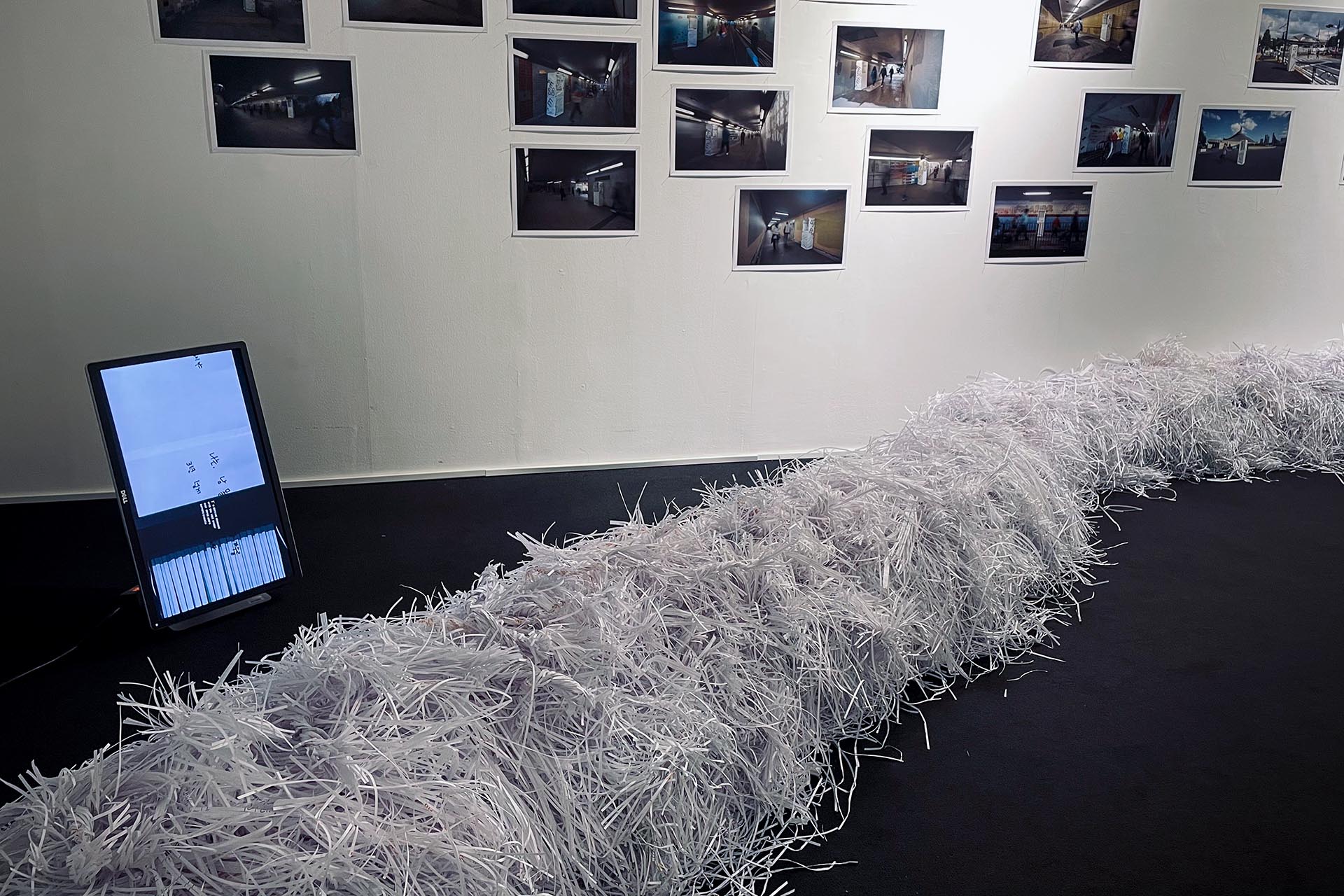

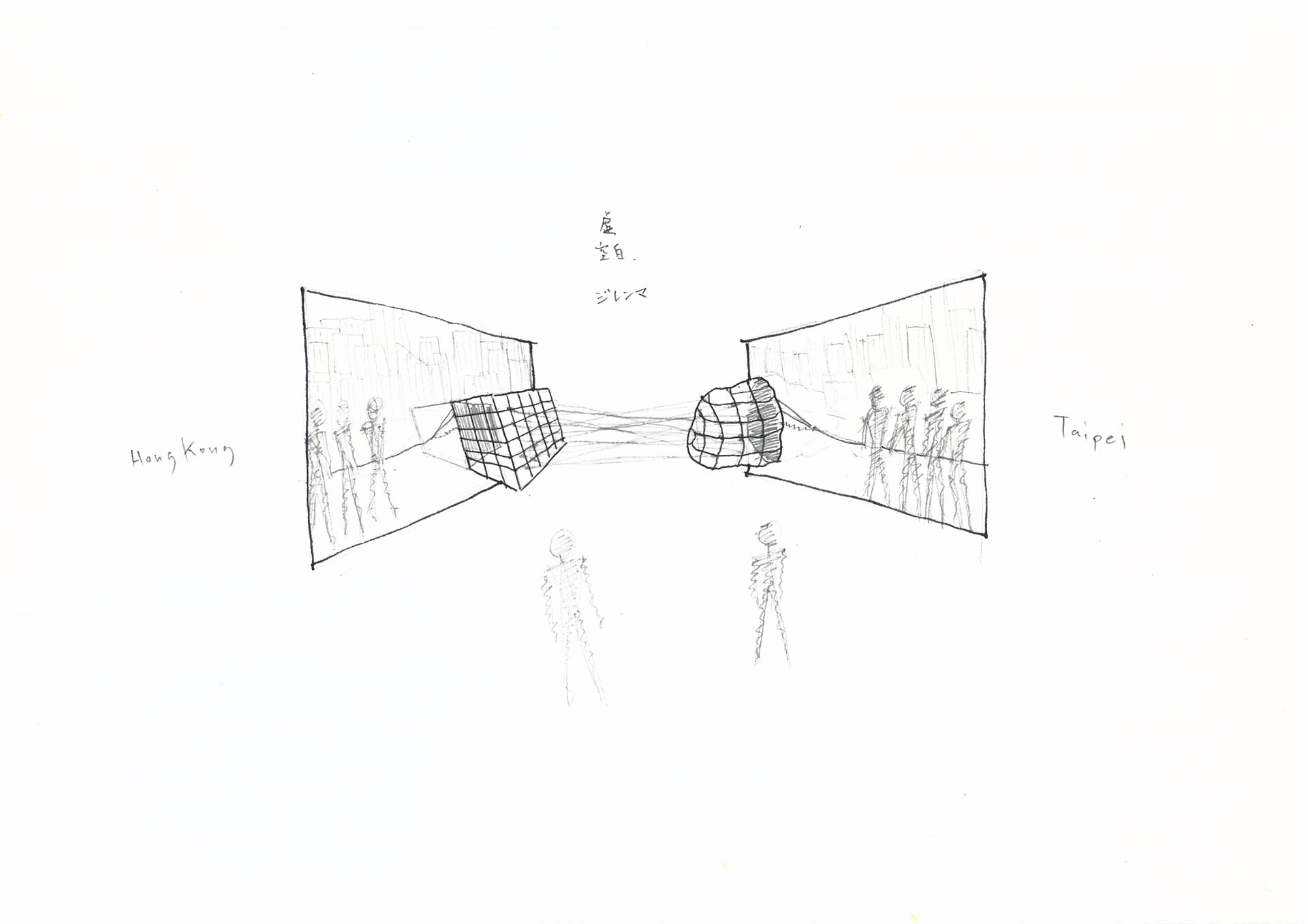

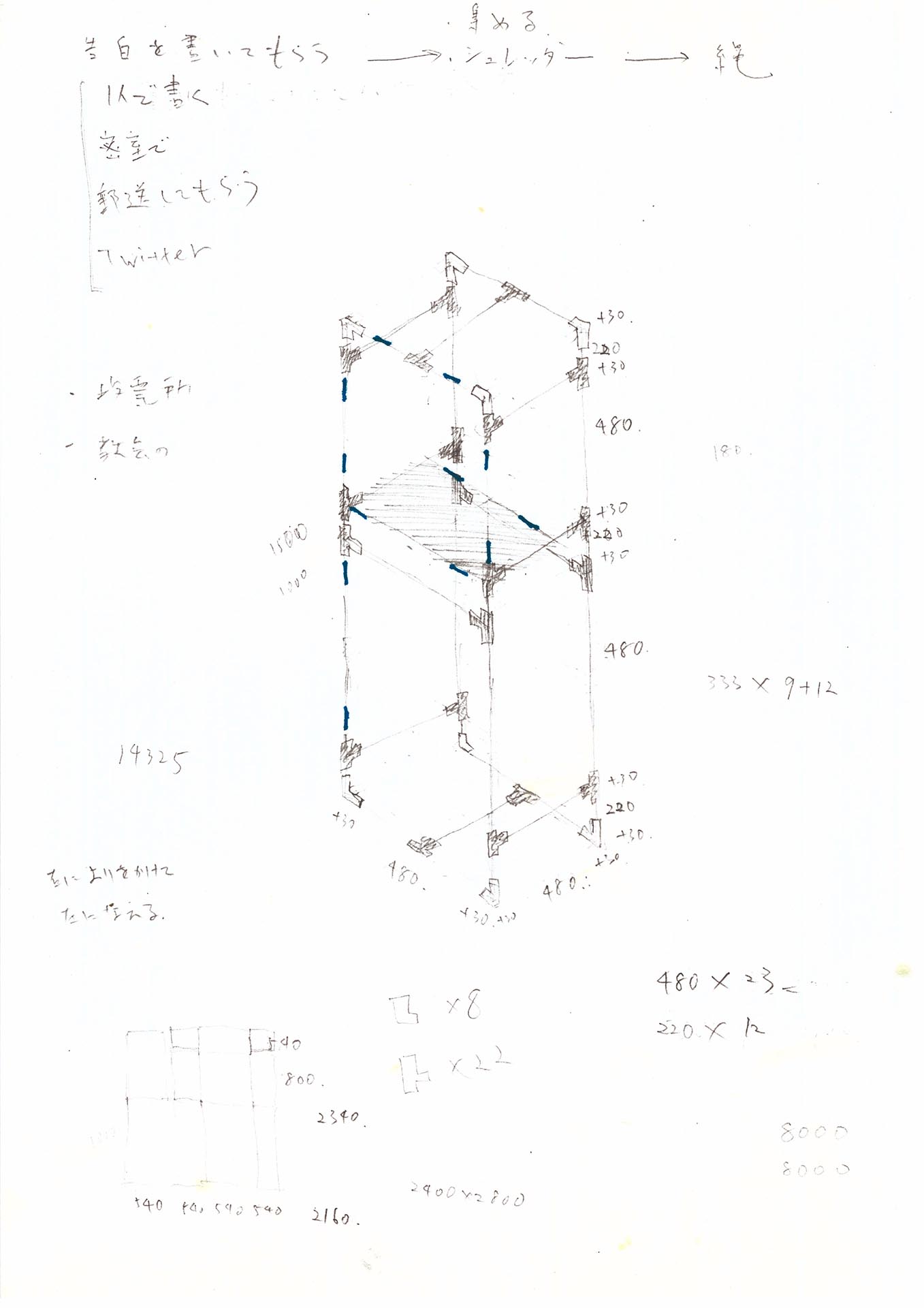

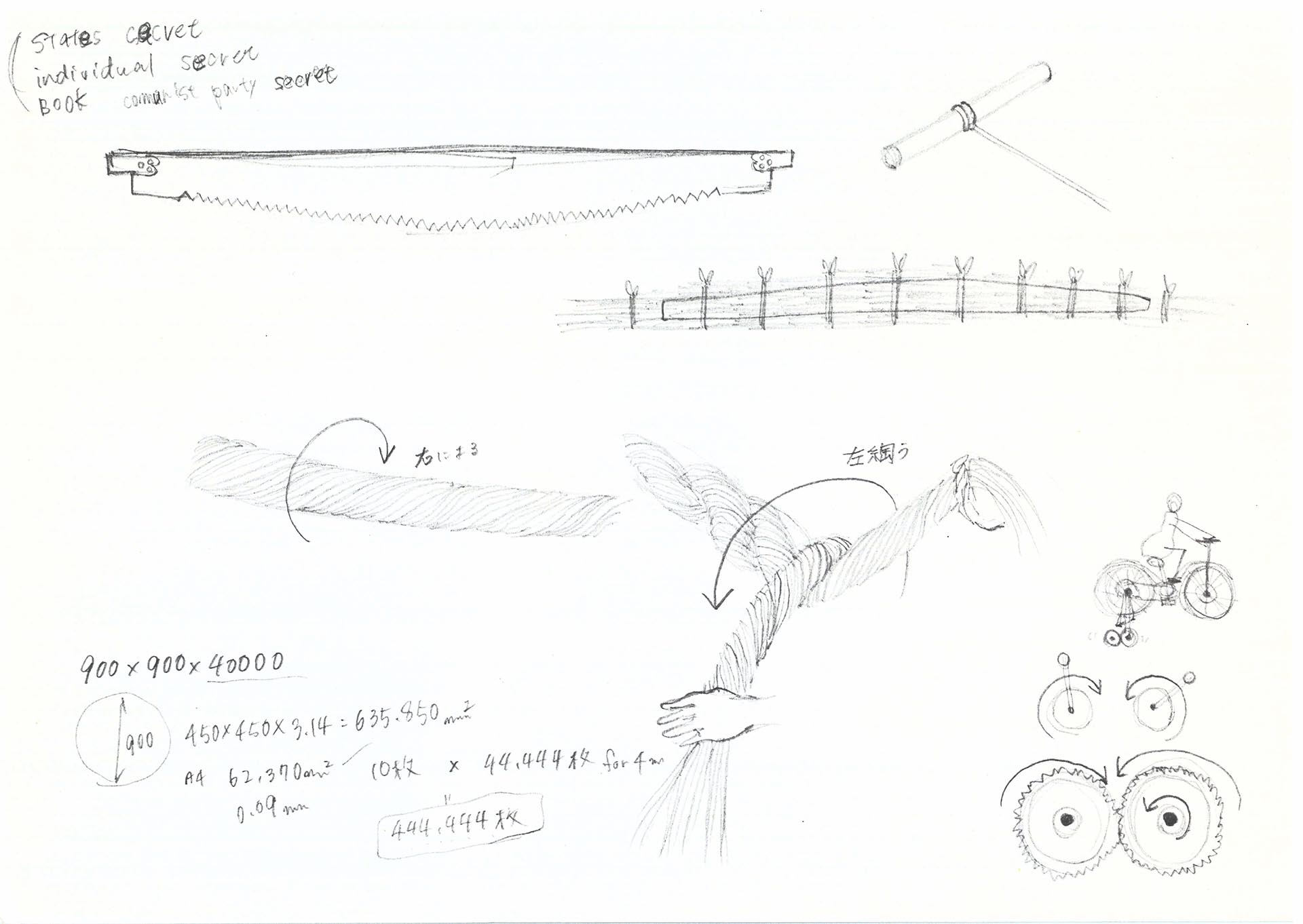

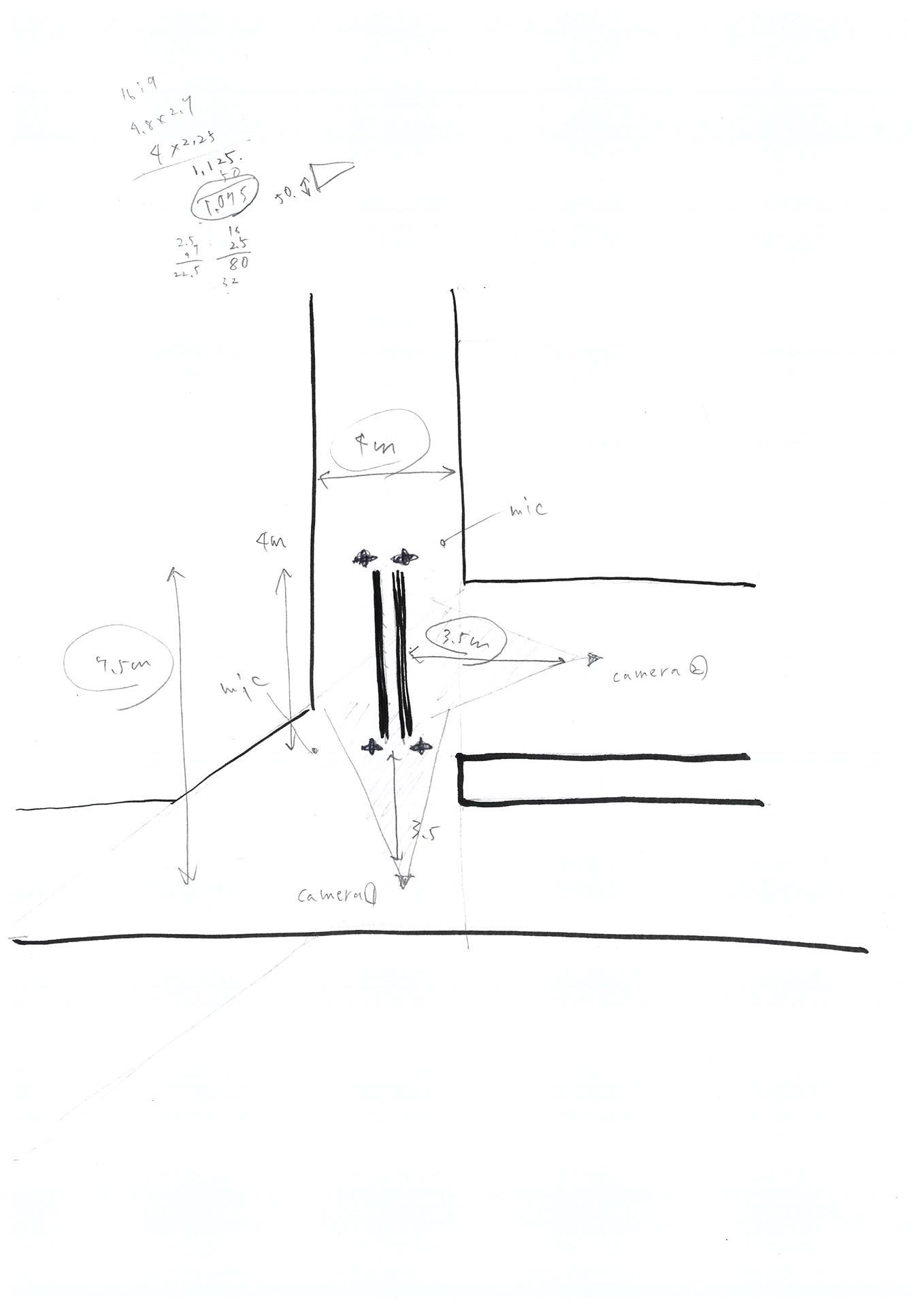

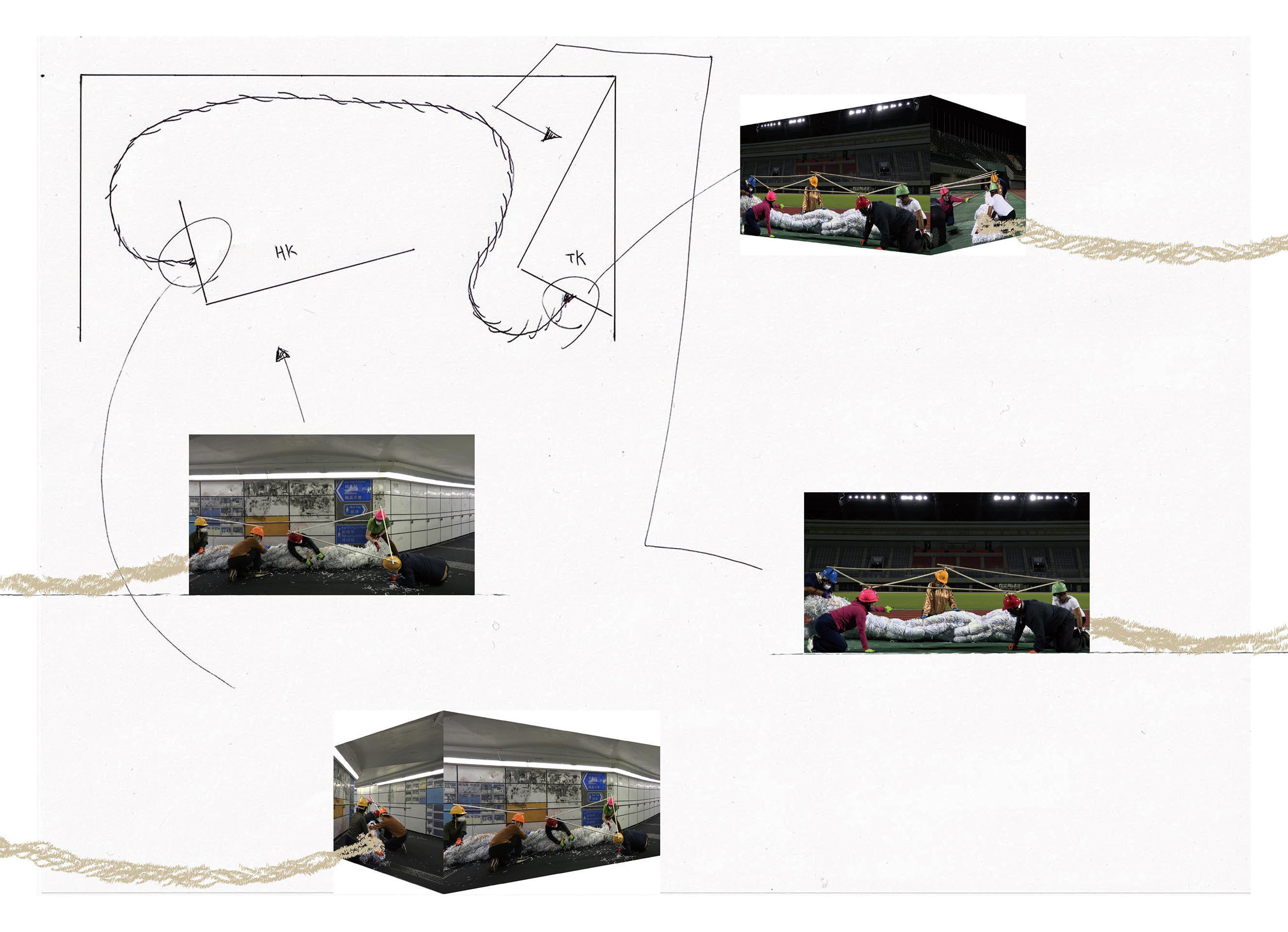

Three videos: two synchronized + one, rope by shredded papers, shredder, and Lambda print

Sound designed by: Sous Chef

Technical supported by: Junnosuke Hara

Construction operated by: Yukari Hirano

Translated by: Tinshui Yeung

Last year, at the Aichi Triennale 2019 (August-October), we witnessed how virulently allergic Japan is to the topics of the “comfort women” and the “Emperor.” The uproar was so great, in fact, that part of the exhibition was closed to the public, reopened for only a week at the end of the festival’s duration. In response, I and other artists created Sanatorium, an alternative space for lectures, roundtables, and dialogues. Among the individuals hosted were Kim Eun-sung and Kim Seo-kyung, the artists of The Statue of a Girl of Peace, and Kawamura Takashi, Mayor of Nagoya city. Since then, I have continued exploring the divide between civil society and certain taboo words and topics.

Then, in November last year, I travelled to Taipei for a group exhibition held at MOCA Taipei. The Hong Kong local elections were going on at the time. Though an ocean away, the ripples of the Hong Kong protests could be felt in Taipei, where I had a chance to talk with young Taiwanese supporters of Hong Kong’s democratic candidates. A few months later, this February, I went to Hong Kong for a group exhibition at Tai Kwun Contemporary. This was a month after the Taiwanese Presidential elections, the results of which emboldened Hong Kong’s young pro-democracy supporters. Taiwan and Hong Kong felt practically like neighbors.

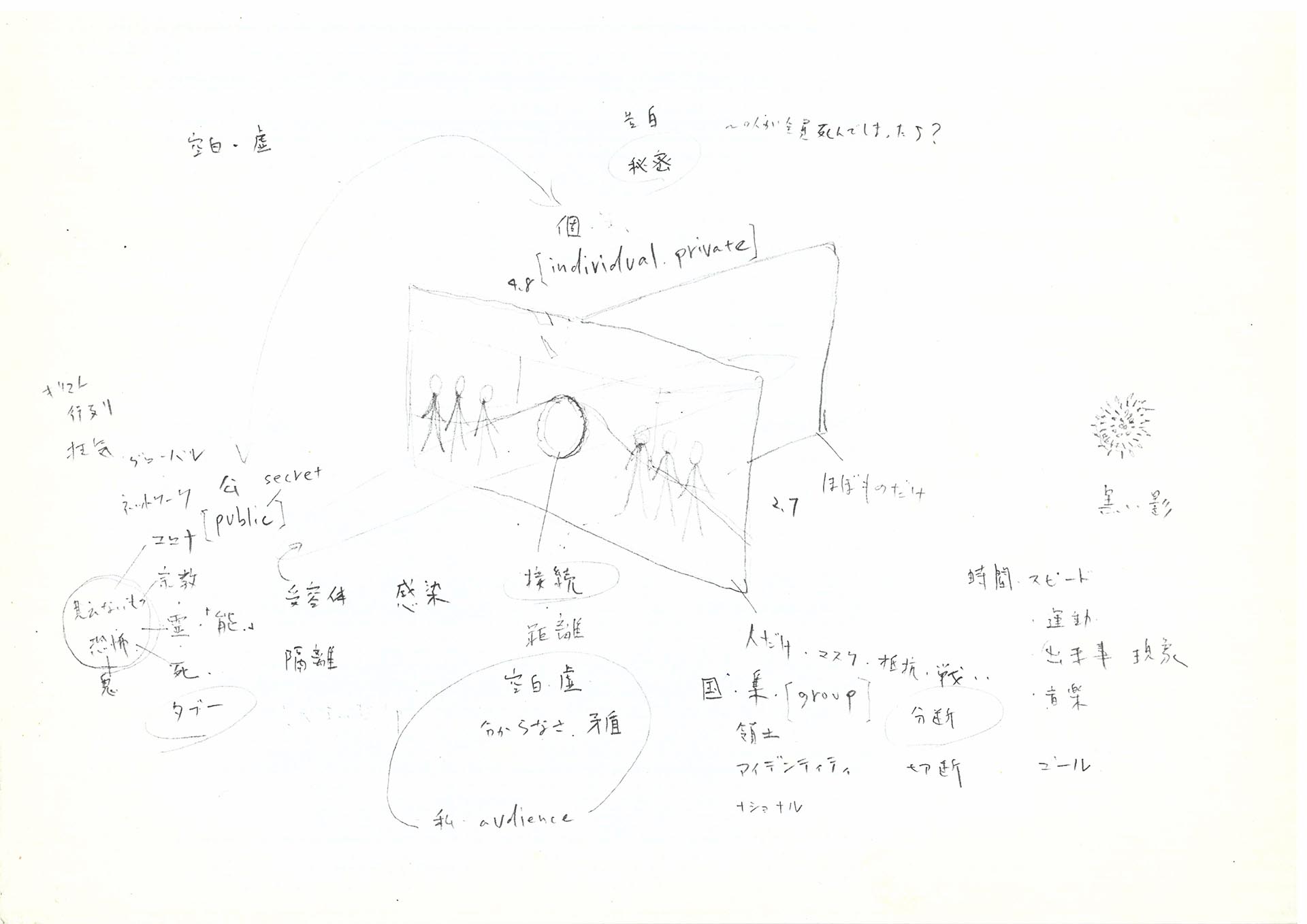

Whether it’s divisions in civil society over certain topics or unity between Taiwanese and Hong Kong youth, it goes without saying that what happened was galvanized by social media. In the first case, social media is a battlefield where you can attack your opponents anonymously. In the other, it’s a platform for coordinating solidarity across national boundaries. How does one capture the double-sidedness of social media as it plays out on the ground in Hong Kong amidst the unfolding of intense pro-democracy protests? That was the question I asked myself as I explored the streets of the city, finding an answer inside the pedestrian tunnels that snake beneath the ground. There, on the walls, you find protestors posting information about upcoming protests—the day, the time, the location—as well as people attempting to stifle the protests by blotting out that information with black paint. What’s interesting about this is that this same information is readily available on social media. Nevertheless, the two sides feel the need to give it a physical presence in public space. The traces of their cat-and-mouse game of updates and deletions can still be seen on the tunnels’ walls. What is this need to transfer information from the space of the internet to physical reality? With that question centrally in my mind, I brought together Hong Kong-based artists, thinkers, and students for a performance inside one of the underground tunnels.

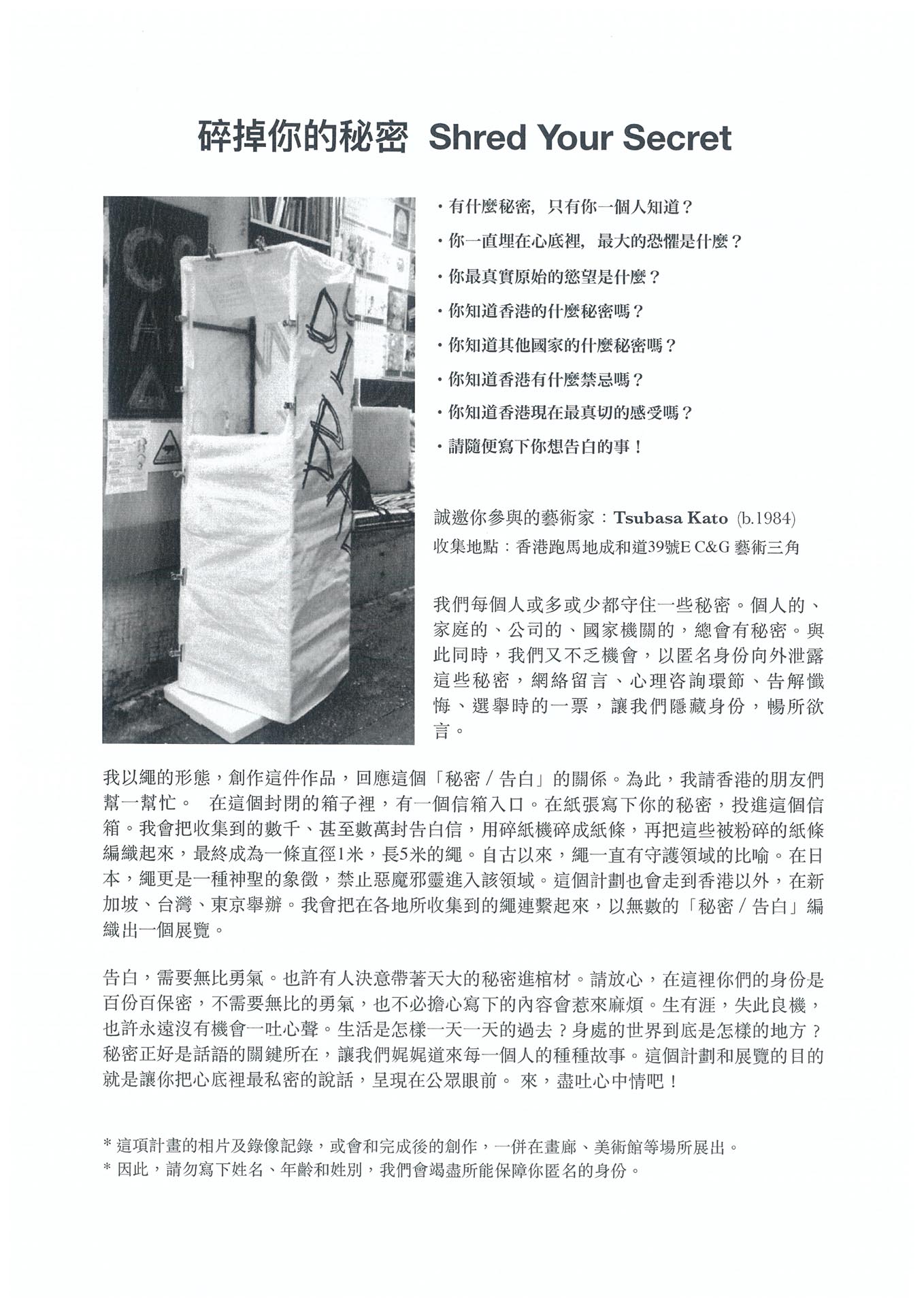

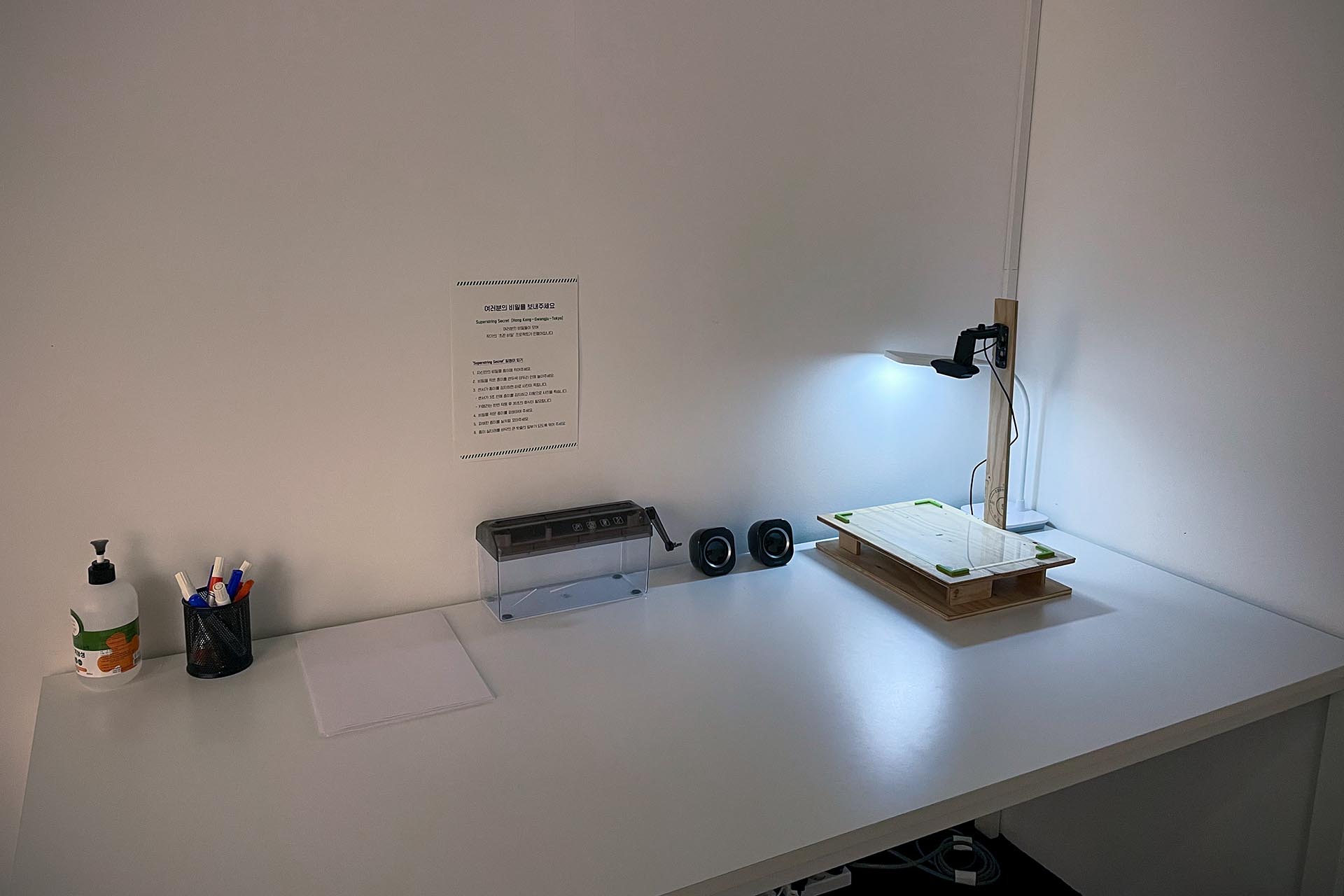

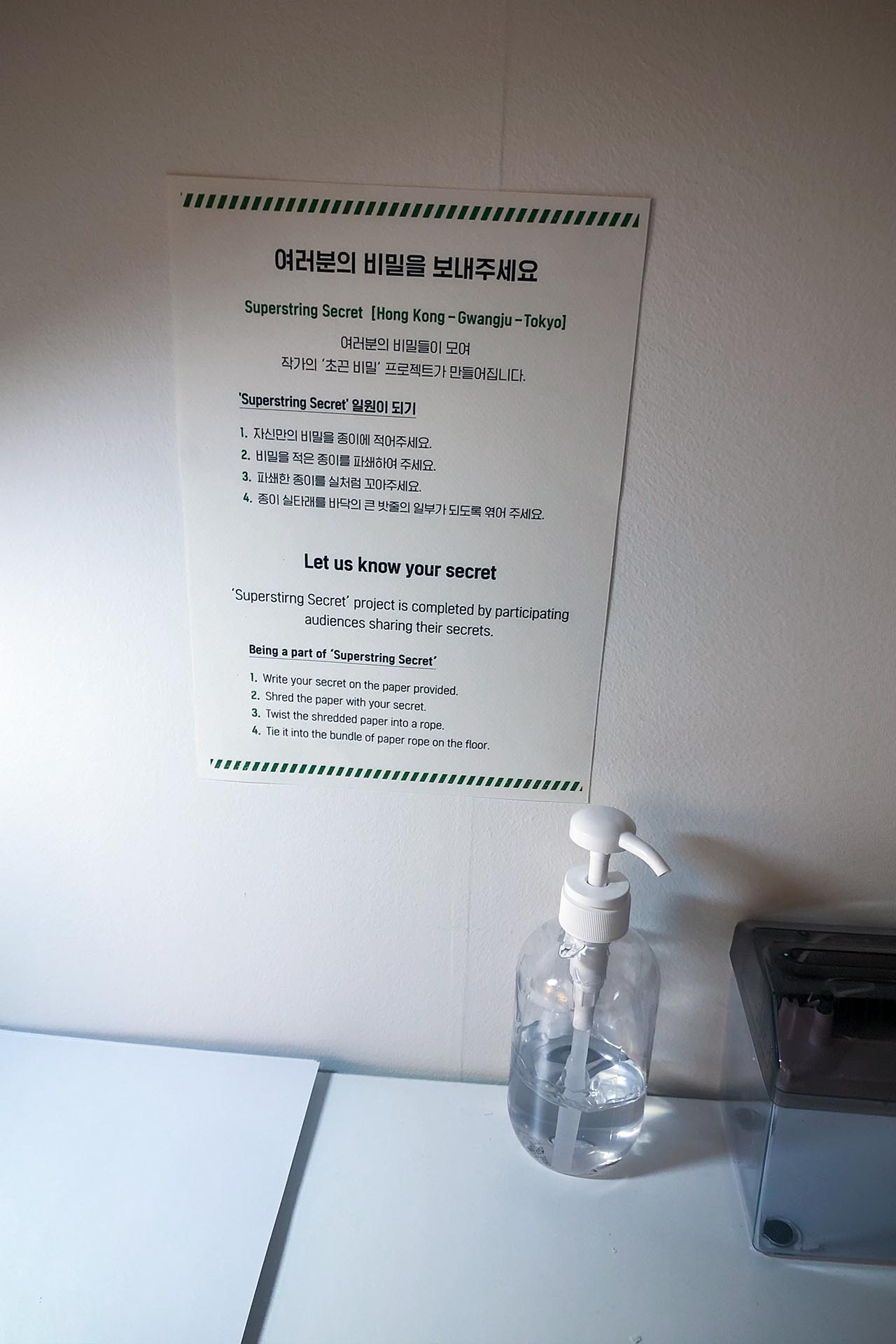

Everyone has secrets. As individuals, as families, as companies, as nations, we all have our secrets (even if those secrets are publicly known). We also have different opportunities to divulge what we keep within us while still maintaining our privacy or anonymity: as comments on the internet, in sessions with psychiatrists, during confession at churches or mosques, as voters during elections. Our secrets are intimately connected to our daily lives and the social environments we move through. Those spaces thus hold the keys to unlocking the stories hidden inside of us. An important feature of this installation is that the secrets are updated as they are collected in different places at different times. In fact, secrets are being collected right now at the Asia Culture Center in Gwangju, South Korea, at a group exhibition being held concurrently with the present solo exhibition. The video on display there will be updated remotely from Tokyo (by use of a camera that automatically photographs each secret written in Gwangju and uploads it to Google Drive, from where they are processed in Tokyo and sent back to Gwangju one at a time). I would like you to imagine this project as unfolding, not just here and now in East Asia, but around the world, creating a landscape across which our secrets are woven together beyond place and time.

Then, in November last year, I travelled to Taipei for a group exhibition held at MOCA Taipei. The Hong Kong local elections were going on at the time. Though an ocean away, the ripples of the Hong Kong protests could be felt in Taipei, where I had a chance to talk with young Taiwanese supporters of Hong Kong’s democratic candidates. A few months later, this February, I went to Hong Kong for a group exhibition at Tai Kwun Contemporary. This was a month after the Taiwanese Presidential elections, the results of which emboldened Hong Kong’s young pro-democracy supporters. Taiwan and Hong Kong felt practically like neighbors.

Whether it’s divisions in civil society over certain topics or unity between Taiwanese and Hong Kong youth, it goes without saying that what happened was galvanized by social media. In the first case, social media is a battlefield where you can attack your opponents anonymously. In the other, it’s a platform for coordinating solidarity across national boundaries. How does one capture the double-sidedness of social media as it plays out on the ground in Hong Kong amidst the unfolding of intense pro-democracy protests? That was the question I asked myself as I explored the streets of the city, finding an answer inside the pedestrian tunnels that snake beneath the ground. There, on the walls, you find protestors posting information about upcoming protests—the day, the time, the location—as well as people attempting to stifle the protests by blotting out that information with black paint. What’s interesting about this is that this same information is readily available on social media. Nevertheless, the two sides feel the need to give it a physical presence in public space. The traces of their cat-and-mouse game of updates and deletions can still be seen on the tunnels’ walls. What is this need to transfer information from the space of the internet to physical reality? With that question centrally in my mind, I brought together Hong Kong-based artists, thinkers, and students for a performance inside one of the underground tunnels.

Everyone has secrets. As individuals, as families, as companies, as nations, we all have our secrets (even if those secrets are publicly known). We also have different opportunities to divulge what we keep within us while still maintaining our privacy or anonymity: as comments on the internet, in sessions with psychiatrists, during confession at churches or mosques, as voters during elections. Our secrets are intimately connected to our daily lives and the social environments we move through. Those spaces thus hold the keys to unlocking the stories hidden inside of us. An important feature of this installation is that the secrets are updated as they are collected in different places at different times. In fact, secrets are being collected right now at the Asia Culture Center in Gwangju, South Korea, at a group exhibition being held concurrently with the present solo exhibition. The video on display there will be updated remotely from Tokyo (by use of a camera that automatically photographs each secret written in Gwangju and uploads it to Google Drive, from where they are processed in Tokyo and sent back to Gwangju one at a time). I would like you to imagine this project as unfolding, not just here and now in East Asia, but around the world, creating a landscape across which our secrets are woven together beyond place and time.