Superstring Secrets: Tokyo

2020

Filmed by Taro Aoishi Sound designed by Sous Chef Translated by Ryan Holmberg Video: 10m 23s

2020

Filmed by Taro Aoishi Sound designed by Sous Chef Translated by Ryan Holmberg Video: 10m 23s

Last year, at the Aichi Triennale 2019 (August-October), we witnessed how virulently allergic Japan is to the topics of the “comfort women” and the “Emperor.” The uproar was so great, in fact, that part of the exhibition was closed to the public, reopened for only a week at the end of the festival’s duration. In response, I and other artists created Sanatorium, an alternative space for lectures, roundtables, and dialogues. Among the individuals hosted were Kim Eun-sung and Kim Seo-kyung, the artists of The Statue of a Girl of Peace, and Kawamura Takashi, Mayor of Nagoya city. Since then, I have continued exploring the divide between civil society and certain taboo words and topics.

Then, in November last year, I travelled to Taipei for a group exhibition held at MOCA Taipei. The Hong Kong local elections were going on at the time. Though an ocean away, the ripples of the Hong Kong protests could be felt in Taipei, where I had a chance to talk with young Taiwanese supporters of Hong Kong’s democratic candidates. A few months later, this February, I went to Hong Kong for a group exhibition at Tai Kwun Contemporary. This was a month after the Taiwanese Presidential elections, the results of which emboldened Hong Kong’s young pro-democracy supporters. Taiwan and Hong Kong felt practically like neighbors.

Whether it’s divisions in civil society over certain topics or unity between Taiwanese and Hong Kong youth, it goes without saying that what happened was galvanized by social media. In the first case, social media is a battlefield where you can attack your opponents anonymously. In the other, it’s a platform for coordinating solidarity across national boundaries. How does one capture the double-sidedness of social media as it plays out on the ground in Hong Kong amidst the unfolding of intense pro-democracy protests? That was the question I asked myself as I explored the streets of the city, finding an answer inside the pedestrian tunnels that snake beneath the ground. There, on the walls, you find protestors posting information about upcoming protests—the day, the time, the location—as well as people attempting to stifle the protests by blotting out that information with black paint. What’s interesting about this is that this same information is readily available on social media. Nevertheless, the two sides feel the need to give it a physical presence in public space. The traces of their cat-and-mouse game of updates and deletions can still be seen on the tunnels’ walls. What is this need to transfer information from the space of the internet to physical reality? With that question centrally in my mind, I brought together Hong Kong- based artists, thinkers, and students for a performance inside one of the underground tunnels.

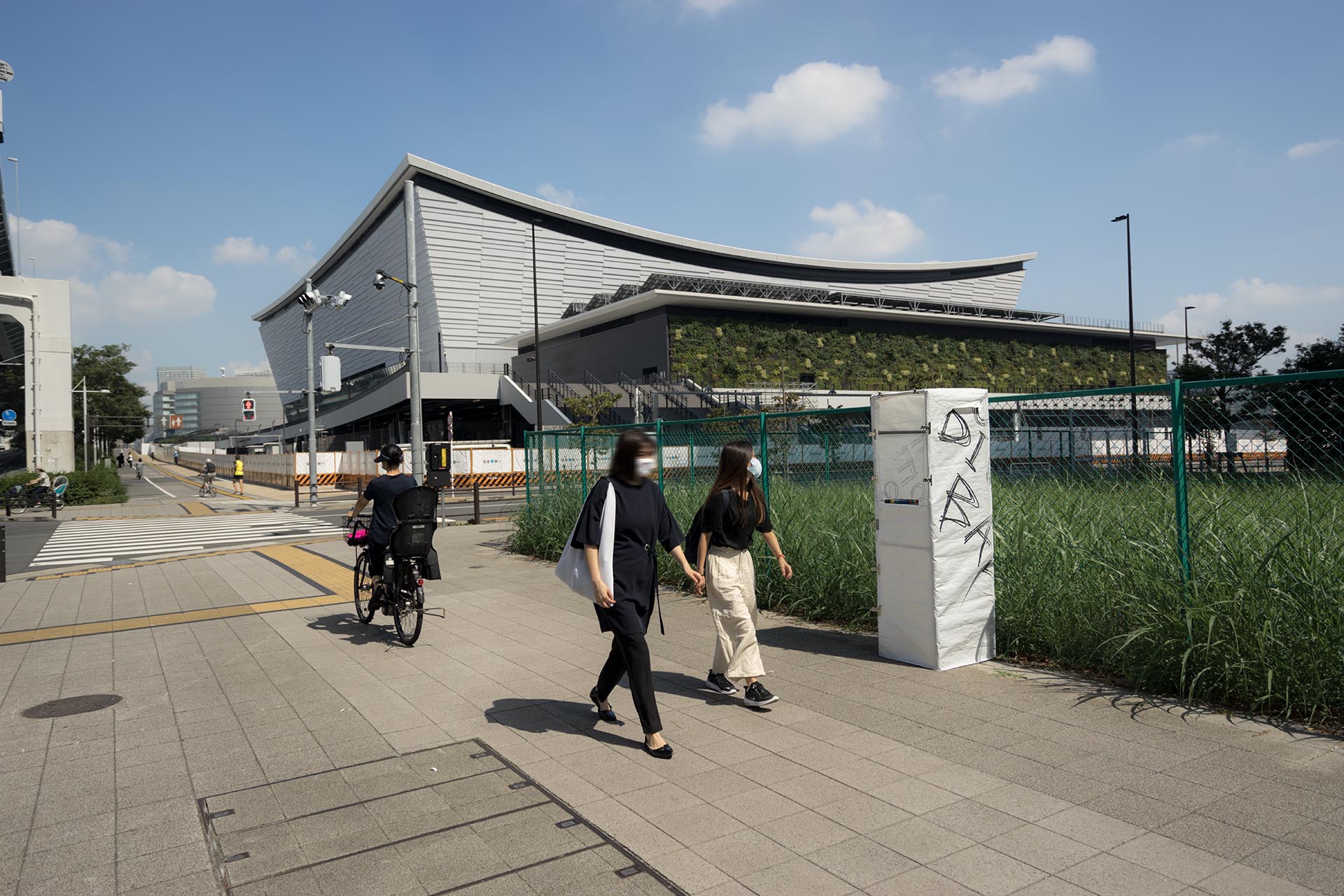

Though I was scheduled to continue this project in Singapore and Taipei, those plans were postponed by the outbreak of COVID-19. I had no choice but to return to Tokyo, which I did in May. I started researching conditions in Tokyo under the pandemic instead. That is when I met some Kurdish people. While travel restrictions and stay- at-home orders were new to most Japanese, people like the Kurds are intimately familiar with limited freedom of movement. While applying for refugee status, for example, they may be given provisional release from the Japanese Immigration Bureau’s detention centers, but they are not allowed to leave the local city or prefecture without special permission. As a result, many of them arrange to meet friends or family members at places like bridges over rivers that separate one prefecture from the next. I was embarrassed that I had no idea something like this was happening in my own country. “Travel restrictions and stay-at-home orders are things already forced upon us,” one Kurdish man told me. With the hope that he would be part of my project, I went with him to the immigration office in Shinagawa, in southern Tokyo, to apply for a temporary travel permit. However, citing COVID-19, his application was denied. Of course, the Japanese government needs immigrants like the Kurds. During the lead-up to the postponed Olympics, for example, when buildings were being pulled down at breakneck speed in Tokyo, many demolition crews were run by Kurds.

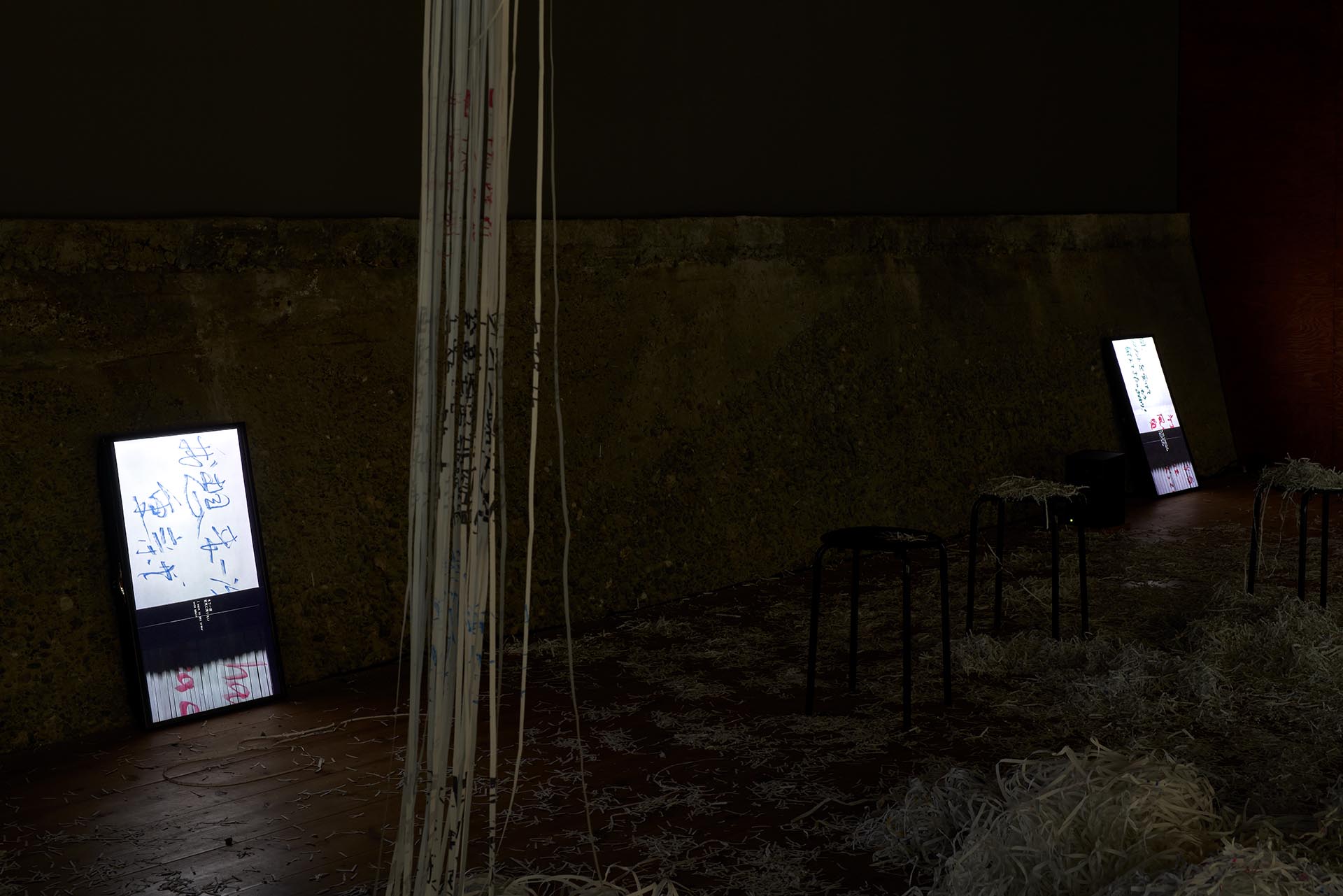

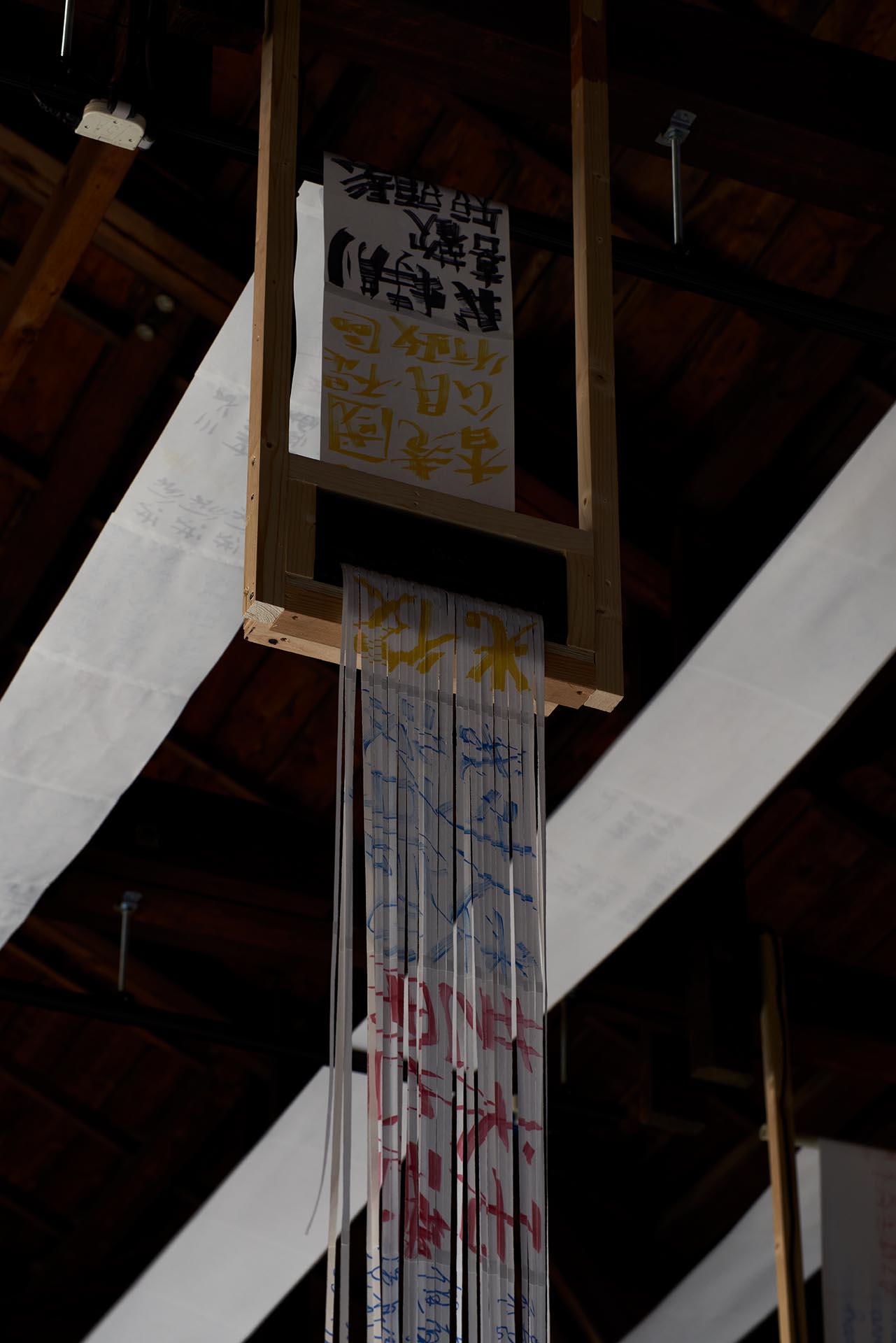

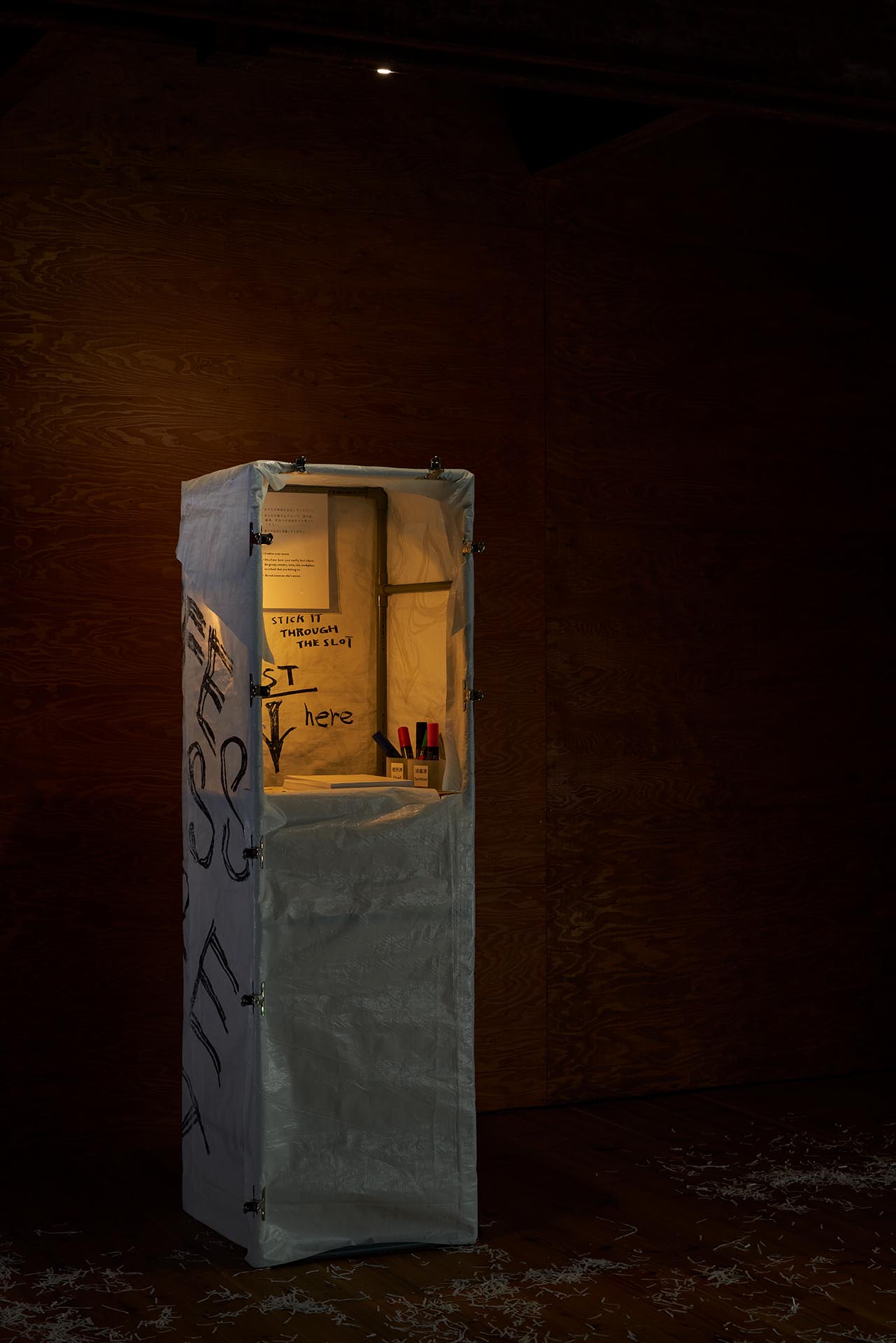

Everyone has secrets. As individuals, as families, as companies, as nations, we all have our secrets (even if those secrets are publicly known). We also have different opportunities to divulge what we keep within us while still maintaining our privacy or anonymity: as comments on the internet, in sessions with psychiatrists, during confession at churches or mosques, as voters during elections. Our secrets are intimately connected to our daily lives and the social environments we move through. Those spaces thus hold the keys to unlocking the stories hidden inside of us. An important feature of this installation is that the secrets are updated as they are collected in different places at different times. In fact, secrets are being collected right now at the Asia Culture Center in Gwangju, South Korea, at a group exhibition being held concurrently with the present solo exhibition. The video on display there will be updated remotely from Tokyo (by use of a camera that automatically photographs each secret written in Gwangju and uploads it to Google Drive, from where they are processed in Tokyo and sent back to Gwangju one at a time). I would like you to imagine this project as unfolding, not just here and now in East Asia, but around the world, creating a landscape across which our secrets are woven together beyond place and time.

「慰安婦」「天皇」といったトピックが強烈なアレルギー反応を起こすさまを目の当たりにさせられた昨年8~10月の国際芸術祭「あいちトリエンナーレ2019」。一部の展示が見れなくなるという騒動から始まり、結果的に一週間だけ展示が再開され、トリエンナーレの閉幕を迎えるまで、複数のアーティストたちとオルタナティブ・スペース「サナトリウム」を立ち上げて「平和の少女像」の作家キム・ウンソン&キム・ソギョンや河村たかし名古屋市長といったゲストを迎えてのレクチャー、座談会、対談を企画した。それ以来、社会のなかである種タブー化されたNGワードといわゆる社会(市民)の分断との関係について着目している。

一方で、昨年11月からはMOCA台北での展覧会のために台北に滞在しはじめ、それはちょうど香港の区議会選挙の最中だった。海を隔てながらも香港プロテストの動向を注視し、香港の民主派候補たちを支援する台北の若者たちと触れあい、年が明けた2月からは香港の大館當代美術館での展覧会のために香港滞在をはじめたが、それは台湾の総統選の翌月のことであり、その結果に少なからず勇気づけられる香港の若者たちの姿に台湾と香港の距離の近さを実感した。

あるトピックをめぐる市民の分断も、台湾と香港の若者たちの結束も、それらを触発するのは言わずもがなソーシャルメディアであり、それは匿名で敵を攻撃しあう戦場となる一方で、国境を超えた団結を演出するプラットフォームにもなっている。苛烈な民主化デモが繰り広げられている香港にそうした両面性を持つ場が現実としてどのように表現されうるのか、と街を探索し、街の地下に張り巡らされている歩行者トンネルで足を止めた。そこには次回のデモのステートメントや集合場所、日付を掲示するプロテスターたちがいれば、反対にそれらの情報を黒塗りにして隠そうとする者たちもいた。興味深いことに、そうした情報はソーシャルメディアで既に共有されているとしても、地下トンネルという公共空間で物質としても共有しなおされ、その情報更新と消去のイタチごっこの痕跡は今もなお壁に残されているのだ。なぜ情報はインターネット空間から現実空間へとわざわざ移送さなければならなかったのか?その疑問自体の発見が今回のプロジェクトの基軸となり、香港で活動するアーティスト、哲学者、学生たちの協力のもと、地下トンネルでのパフォーマンスを撮影した。

今回のプロジェクト・シリーズは香港の後、シンガポールと台北でも計画されていたがパンデミックの影響で両方とも延期されてしまった。仕方なしに5月に帰国し、代わりにパンデミック下の東京のリサーチを始めたとき、クルド人の人たちと出会うことができた。パンデミックによって渡航制限や外出自粛のような移動制限が私たちに課される以前に、例えば難民申請中で出入国在留管理庁の入国者収容所から仮放免の状態下にある人たちは、許可がなければ自由に都外・県外に出ることをそもそも禁止されている。隣の県に住む家族や友人とその県境の川に架かる橋でしか落ち合えないという現状がこの日本で繰り広げられていることすら、恥ずかしながら僕は知らなかった。「常に私たちは自粛することを強いられてきた」と語ってくれた男性にこのプロジェクトに協力してもらうため、品川の入国管理局に一緒に行き彼の外出許可を申請したが、パンデミック下であることを理由にその許可はおりなかった。秘密裏に建設解体業を営む多くのクルド人の人たちがオリンピックによる東京の解体ラッシュの立役者であることは、間違いない。

誰しもが何かしらかの秘密を個人としてだけではなく、家族でも、会社でも、国家単位でも(たとえそれが公然の秘密だとしても)抱え、例えばインターネットの掲示板、心療カウンセラーとのインタビュー、モスクや教会での懺悔、選挙投票などの機会において、匿名性が守られつつ私たちは内なる思いを吐き出すことができる。秘密は、私たちがどのような日常を過ごしているのか、私たちを取り巻く環境がどのような場所なのかに密接的に関わり、それ故に私たちの物語を紐解くことができる鍵である。このインスタレーションの特徴は、秘密を集める時代や場所を変えながらその内容がアップデートされていく点にある。現に、この個展と同時期に開催する韓国・光州のACC(アジア・カルチャー・センター)での展覧会においても秘密を集め、そのインスタレーションで流れる映像を東京から遠隔で更新していく(展覧会場には、書かれた秘密を自動で撮影しGoogleドライブにアップロードするカメラが設置され、そのデータを東京で受け取り、更新した映像を光州に逐一送っていく)。このプロジェクトが今の東アジアだけでなく、やがて世界各地に展開し、時代を超えて私たちの秘密を紡いでいく風景を想像してもらいたい。

Then, in November last year, I travelled to Taipei for a group exhibition held at MOCA Taipei. The Hong Kong local elections were going on at the time. Though an ocean away, the ripples of the Hong Kong protests could be felt in Taipei, where I had a chance to talk with young Taiwanese supporters of Hong Kong’s democratic candidates. A few months later, this February, I went to Hong Kong for a group exhibition at Tai Kwun Contemporary. This was a month after the Taiwanese Presidential elections, the results of which emboldened Hong Kong’s young pro-democracy supporters. Taiwan and Hong Kong felt practically like neighbors.

Whether it’s divisions in civil society over certain topics or unity between Taiwanese and Hong Kong youth, it goes without saying that what happened was galvanized by social media. In the first case, social media is a battlefield where you can attack your opponents anonymously. In the other, it’s a platform for coordinating solidarity across national boundaries. How does one capture the double-sidedness of social media as it plays out on the ground in Hong Kong amidst the unfolding of intense pro-democracy protests? That was the question I asked myself as I explored the streets of the city, finding an answer inside the pedestrian tunnels that snake beneath the ground. There, on the walls, you find protestors posting information about upcoming protests—the day, the time, the location—as well as people attempting to stifle the protests by blotting out that information with black paint. What’s interesting about this is that this same information is readily available on social media. Nevertheless, the two sides feel the need to give it a physical presence in public space. The traces of their cat-and-mouse game of updates and deletions can still be seen on the tunnels’ walls. What is this need to transfer information from the space of the internet to physical reality? With that question centrally in my mind, I brought together Hong Kong- based artists, thinkers, and students for a performance inside one of the underground tunnels.

Though I was scheduled to continue this project in Singapore and Taipei, those plans were postponed by the outbreak of COVID-19. I had no choice but to return to Tokyo, which I did in May. I started researching conditions in Tokyo under the pandemic instead. That is when I met some Kurdish people. While travel restrictions and stay- at-home orders were new to most Japanese, people like the Kurds are intimately familiar with limited freedom of movement. While applying for refugee status, for example, they may be given provisional release from the Japanese Immigration Bureau’s detention centers, but they are not allowed to leave the local city or prefecture without special permission. As a result, many of them arrange to meet friends or family members at places like bridges over rivers that separate one prefecture from the next. I was embarrassed that I had no idea something like this was happening in my own country. “Travel restrictions and stay-at-home orders are things already forced upon us,” one Kurdish man told me. With the hope that he would be part of my project, I went with him to the immigration office in Shinagawa, in southern Tokyo, to apply for a temporary travel permit. However, citing COVID-19, his application was denied. Of course, the Japanese government needs immigrants like the Kurds. During the lead-up to the postponed Olympics, for example, when buildings were being pulled down at breakneck speed in Tokyo, many demolition crews were run by Kurds.

Everyone has secrets. As individuals, as families, as companies, as nations, we all have our secrets (even if those secrets are publicly known). We also have different opportunities to divulge what we keep within us while still maintaining our privacy or anonymity: as comments on the internet, in sessions with psychiatrists, during confession at churches or mosques, as voters during elections. Our secrets are intimately connected to our daily lives and the social environments we move through. Those spaces thus hold the keys to unlocking the stories hidden inside of us. An important feature of this installation is that the secrets are updated as they are collected in different places at different times. In fact, secrets are being collected right now at the Asia Culture Center in Gwangju, South Korea, at a group exhibition being held concurrently with the present solo exhibition. The video on display there will be updated remotely from Tokyo (by use of a camera that automatically photographs each secret written in Gwangju and uploads it to Google Drive, from where they are processed in Tokyo and sent back to Gwangju one at a time). I would like you to imagine this project as unfolding, not just here and now in East Asia, but around the world, creating a landscape across which our secrets are woven together beyond place and time.

「慰安婦」「天皇」といったトピックが強烈なアレルギー反応を起こすさまを目の当たりにさせられた昨年8~10月の国際芸術祭「あいちトリエンナーレ2019」。一部の展示が見れなくなるという騒動から始まり、結果的に一週間だけ展示が再開され、トリエンナーレの閉幕を迎えるまで、複数のアーティストたちとオルタナティブ・スペース「サナトリウム」を立ち上げて「平和の少女像」の作家キム・ウンソン&キム・ソギョンや河村たかし名古屋市長といったゲストを迎えてのレクチャー、座談会、対談を企画した。それ以来、社会のなかである種タブー化されたNGワードといわゆる社会(市民)の分断との関係について着目している。

一方で、昨年11月からはMOCA台北での展覧会のために台北に滞在しはじめ、それはちょうど香港の区議会選挙の最中だった。海を隔てながらも香港プロテストの動向を注視し、香港の民主派候補たちを支援する台北の若者たちと触れあい、年が明けた2月からは香港の大館當代美術館での展覧会のために香港滞在をはじめたが、それは台湾の総統選の翌月のことであり、その結果に少なからず勇気づけられる香港の若者たちの姿に台湾と香港の距離の近さを実感した。

あるトピックをめぐる市民の分断も、台湾と香港の若者たちの結束も、それらを触発するのは言わずもがなソーシャルメディアであり、それは匿名で敵を攻撃しあう戦場となる一方で、国境を超えた団結を演出するプラットフォームにもなっている。苛烈な民主化デモが繰り広げられている香港にそうした両面性を持つ場が現実としてどのように表現されうるのか、と街を探索し、街の地下に張り巡らされている歩行者トンネルで足を止めた。そこには次回のデモのステートメントや集合場所、日付を掲示するプロテスターたちがいれば、反対にそれらの情報を黒塗りにして隠そうとする者たちもいた。興味深いことに、そうした情報はソーシャルメディアで既に共有されているとしても、地下トンネルという公共空間で物質としても共有しなおされ、その情報更新と消去のイタチごっこの痕跡は今もなお壁に残されているのだ。なぜ情報はインターネット空間から現実空間へとわざわざ移送さなければならなかったのか?その疑問自体の発見が今回のプロジェクトの基軸となり、香港で活動するアーティスト、哲学者、学生たちの協力のもと、地下トンネルでのパフォーマンスを撮影した。

今回のプロジェクト・シリーズは香港の後、シンガポールと台北でも計画されていたがパンデミックの影響で両方とも延期されてしまった。仕方なしに5月に帰国し、代わりにパンデミック下の東京のリサーチを始めたとき、クルド人の人たちと出会うことができた。パンデミックによって渡航制限や外出自粛のような移動制限が私たちに課される以前に、例えば難民申請中で出入国在留管理庁の入国者収容所から仮放免の状態下にある人たちは、許可がなければ自由に都外・県外に出ることをそもそも禁止されている。隣の県に住む家族や友人とその県境の川に架かる橋でしか落ち合えないという現状がこの日本で繰り広げられていることすら、恥ずかしながら僕は知らなかった。「常に私たちは自粛することを強いられてきた」と語ってくれた男性にこのプロジェクトに協力してもらうため、品川の入国管理局に一緒に行き彼の外出許可を申請したが、パンデミック下であることを理由にその許可はおりなかった。秘密裏に建設解体業を営む多くのクルド人の人たちがオリンピックによる東京の解体ラッシュの立役者であることは、間違いない。

誰しもが何かしらかの秘密を個人としてだけではなく、家族でも、会社でも、国家単位でも(たとえそれが公然の秘密だとしても)抱え、例えばインターネットの掲示板、心療カウンセラーとのインタビュー、モスクや教会での懺悔、選挙投票などの機会において、匿名性が守られつつ私たちは内なる思いを吐き出すことができる。秘密は、私たちがどのような日常を過ごしているのか、私たちを取り巻く環境がどのような場所なのかに密接的に関わり、それ故に私たちの物語を紐解くことができる鍵である。このインスタレーションの特徴は、秘密を集める時代や場所を変えながらその内容がアップデートされていく点にある。現に、この個展と同時期に開催する韓国・光州のACC(アジア・カルチャー・センター)での展覧会においても秘密を集め、そのインスタレーションで流れる映像を東京から遠隔で更新していく(展覧会場には、書かれた秘密を自動で撮影しGoogleドライブにアップロードするカメラが設置され、そのデータを東京で受け取り、更新した映像を光州に逐一送っていく)。このプロジェクトが今の東アジアだけでなく、やがて世界各地に展開し、時代を超えて私たちの秘密を紡いでいく風景を想像してもらいたい。